Maxwell Doig - "The Studio Visit."

Critical essay by Jo Manby (Art Critic, Writer)

Driving over rolling hills, folded and scored by the movement of water and ancient tectonic shifts, the landscape shadowed and highlighted in ochres and slate grey, we arrive at Maxwell Doig’s house. His studio is in an upper floor room with a good light, the walls populated by his single figures in mixed media on canvas and paper, the wooden floorboards distressed by paint scattered there as a by-product of his painterly techniques. Books that tell of his artistic influences are stacked on the floor: Frances Spalding’s new monograph on Prunella Clough, ‘Regions Unmapped’; others on Vilhelm Hammershoi and Andrew Wyeth. It is always a pleasure to visit an artist’s studio, as one attempts to absorb with what substance and material the artist forges his or her work, and here I wanted to find out what contributed to the way Doig is able to summon up images of such enigmatic quality. |

Doig tells me about leaving school at 16 and completing a vocational course in a range of artistic subjects such as textiles, graphics and ceramics, in Batley near Leeds. From there he met David Blackburn, a long-standing friend and mentor who is also a painter and a collector of art. He owned pieces by Clough, her painting ‘Grid 4’ being the first example of her work that Doig saw, back in the mid-1980s. This was a significant and enlightening moment for Doig. Later on in the afternoon, he tells me that he met Clough at a retrospective exhibition of her work at Kettle’s Yard in 1999 and that they had discussed swapping work with one another. In 1990, as a student, he met her at a preview of a Keith Vaughan exhibition and was thrilled to be invited to her house for tea the following week; “I found her generous with her time and helpful”. There are common aspects to their work, such as the way both artists turn away from romanticism, focusing on the gritty reality of life, without, however, veering into social realism. They are both persistently digging for visual structure and tying it closely with the nature of their subject matter. |

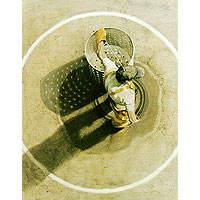

In Doig’s case, the single figure seen from above has become a leitmotif in his work. The single figures are imbued with a sense of solitariness, not loneliness or isolation. They are enclosed and sealed within the ‘safe’ confines of the picture plane and its rectangular frame. Self-contained, they can get on with their own thoughts behind their hats, their newspapers, or their averted gaze, while the artist orders the structure and form of the painting around them. Their stillness and quietude means that rather than standing out from their surroundings, they begin to merge with them, opening and folding like beautiful moths on the bark of a tree. |

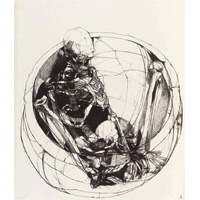

From a fine art degree at Manchester Metropolitan University, Doig went on to study at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London (UCL). The Petrie Museum, named after the renowned Egyptologist Flinders Petrie, is also part of UCL. Doig came across there a 4,000-year-old Egyptian skeleton in a burial pot – effectively a figure within a circle. The resulting work, an impressive monochrome lithograph from 1989, hangs on a wall downstairs at Doig’s house. This was the first in an enduring pursuit of the idea of a human body encircled, almost housed by a physical or symbolic outer structure, even sometimes literally just a circle, as can be seen in the paintings of Breton fishermen from 2004. |

Rectangles and squares are also used. Figures emerge from manholes, work at the top of telegraph poles, sunbathe amidst the right angles of a roof terrace, as in ‘Sunbather, San Francisco II’ (1998). These geometrical shapes help to unify the overall compositions and give the finished paintings a sense of order, whilst at the same time anchoring the figures to the ground and to their surroundings. Looking back at works from across Doig’s career, one has the impression of a coherent body of work built up over time that makes sense as a whole. Doig says that for years he unconsciously worked on similar, recurring themes, but that now, it is more a conscious process. There is mileage in each stage of the continuum that is his oeuvre. Early influences have proved to have lasting effects, inspiring him even today. He cites the example of the anatomy class, “a highlight” of art college. Anatomy classes were optional, but Doig took them at every opportunity. A doctor – an anatomist – led the dissection of cadavers for the students. Doig speaks vividly of the experience of watching the expert opening and revealing the workings of the ribcage.

|

During our discussion we return to ‘Skeleton in a Burial Pot’ as one of the first works to concentrate on an aerial viewpoint. This perspective Doig began in earnest in 1996 with ‘Self portrait drawing a textile worker’. New work on the walls of Doig’s studio is executed on thick, grainy paper using layers of acrylic and diffuser techniques to spray on the paint. In one particular work, ‘Night Swimmer 4’ (2012), the figure with only the top of his head emerging from the dark water, has a blue circle painted round the bald crown of his head which is the blue strap of the pair of goggles the swimmer is wearing. It looks like a halo, which prompted me to ask Doig about the spiritual side of his work. He agreed, “the aerial view allows the familiar to be seen in an unfamiliar way; a cylindrical vat can be read as a circle or a person’s shadow can be read as an abstract pattern. In putting these different elements together within a rectangle, in an ordered way, I’m trying to achieve a sense of balance and order which, hopefully, has a spiritual quality.” I note that the ‘Figure Sleeping Under Blanket’ (2013), who appears to be running, is like an angel on a Renaissance ceiling, with classical drapery in the celestial colours of white and blue. “The aerial view and the pose allow the sleeping figure to be read as a running figure and in turn this might suggest all kinds of things to the viewer. The titles,” says Doig, “are deliberately bland, to avoid putting my own narrative on the work. It’s much more about the pose or posture feeling right. I knew at an early stage, that when working with the human figure, that if I could feel the pose in my own body then, somehow, the drawing or painting would be more convincing because it was more felt.” |

We look at how the day bed the figure is asleep on is only sketchily present and how Doig feels he has put down enough of its structure to establish what the rest of it is like; the rest of it is implicit – a passage occupying most of the right-hand side of the picture (which is portrait format) and is composed of a muted dark blue colour with no detail picked out at all. Dependent on the viewer’s perspective, one knows it is a bed but it is also just paint: a pure, aesthetic, symbolic space devoid of measurable scale or depth, but filled with spiritual presence. I ask Doig if he finds painting very absorbing. Does he lose himself in it? “I’m not in the future and not in the past,’ he replies. “I’m in the present moment, painting”. |

|